Re-Wiring for Progress

Why Britain keeps blocking its own recovery and the institutional reset needed to escape decline

This article is adapted from an original piece by Mark E. Thomas (November 2020). It is just as relevant now as it was in 2020 because the institutional hard-wiring is now standing in the way of Labour’s plans for national renewal.

For most of the 20th century, the UK more or less assumed that each generation would be better off than the last. Growth might rise or fall year to year, but over time, living standards moved upwards. That expectation held until the Global Financial Crisis.

Since 2008, however, something historic has happened: real incomes have stagnated or fallen, and Britain has entered its longest period of wage decline in 100+ years. Public services are strained to breaking point; national infrastructure is visibly decaying; and climate commitments are repeatedly delayed or watered-down.

The problem now goes deeper than simply “bad policy.” The UK has become institutionally hard-wired for regress; that is, our most critical public and quasi-public institutions have developed habits and incentives that trap us in low growth, underinvestment, and pessimism. Even when a government wants change - even if the next government is elected on a mandate to “renew” the country, the system pushes in the opposite direction.

This matters urgently, because as a 2025 election approaches, the public mood is clear: people want renewal, not just stability. But no amount of political will can deliver renewal unless the underlying wiring is changed. Without rewiring, any incoming administration risks becoming another version of the Truss government, blocked by the very system it is trying to operate through.

The institutional roots of stagnation

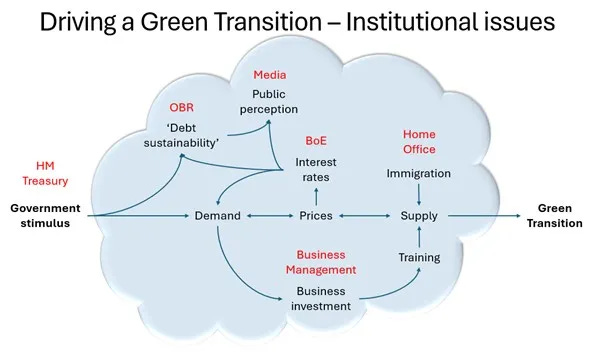

The first piece of wiring is the Treasury. Its worldview remains steeped in market fundamentalism; the private sector should drive everything that can conceivably be market-delivered, and the state should intervene only minimally. That worldview discourages public investment and treats expenditure not as a tool for national renewal, but as a threat to fiscal purity. The Treasury has not absorbed the lesson that a modern state cannot compete globally while underfunding its foundations.

Next comes the Bank of England. Its mandate is almost singular: target two per cent inflation through the blunt instrument of interest rates. When Britain’s recent inflation was driven largely by supply shocks, the Bank still responded by tightening household budgets and restraining investment. The unintended consequence is that inflation control has been pursued at the cost of economic vitality. A single-instrument approach inevitably produces a narrow outcome: weaker growth, suppressed demand and more strain on households.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, meanwhile, has been assigned a similarly constricted remit to ensure that government policy does not violate fiscal rules designed around controlling debt. What it does not assess is the sustainability of the state in any broader sense. The OBR will warn soberly about projected debt levels in 50 years’ time but will not sound equivalent alarm bells about collapsing public infrastructure, local government insolvency or hospitals failing in the present decade.

Business behaviour has been shaped by this stagnation as well. Sixteen years of weak growth have produced an economy in which executives believe investment is structurally unsafe. They will invest in cost-cutting, not capacity. They expect government plans to fizzle out before they scale. They have adapted to low ambition, because recent history has trained them to expect it.

The Home Office contributes its own form of institutional drag by restricting the very labour the economy most needs: the technicians, retrofitters, engineers and construction workers required for a green transition or large-scale infrastructure renewal. Only high-salary immigration is welcomed, the workforce needed for actual delivery is blocked.

Add to this a media ecosystem dominated by a small group of billionaire owners who shape public debate through a lens of austerity, hostility to public investment and suspicion of state-led renewal, and the picture becomes clearer. Each major institution individually nudges the country away from progress, but together they form a barrier system that makes deep reform look reckless or impossible.

The Truss cautionary tale

Liz Truss’s downfall was not caused only by the substance of her policies. It was also a demonstration of what happens when a government announces large-scale change without rewiring the institutional environment first. The moment her plans clashed with Treasury doctrine, investor scepticism, orthodox commentary and OBR framing, the project collapsed.

The same would happen to any large-scale economic transformation, even one far more carefully designed. Consider a future government that tries to insulate Britain’s housing stock at scale. The Treasury would restrict direct public delivery; business would raise prices rather than invest in training; the Home Office would block additional labour; inflation would rise in the short term; the Bank would respond by tightening again; the OBR would warn about fiscal risk; and the media would denounce the plan as economic irresponsibility. A good idea would fail not on its merits, but on the wiring of the system.

Re-wiring the state

If Britain wants renewal, it must reshape its institutions so that they enable progress rather than inhibit it.

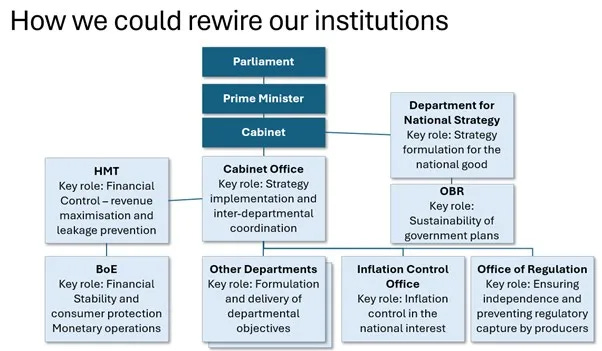

The first required shift is strategic capacity. Britain needs a Department for National Strategy with the explicit remit to think long-term and coordinate whole-economy transformation. Unlike comparable nations such as Singapore or even the EU Commission, the UK does not currently possess any central body structurally focused on the future.

The Cabinet Office would then take responsibility for delivery - translating strategy into practical plans, coordinating departments and ensuring cross-government implementation. The Treasury’s role would shrink to the areas where it genuinely excels: revenue generation and preventing leakage through tax avoidance, evasion and value extraction.

The Bank of England would cease to be the sole custodian of inflation control. A new Inflation Control Office, insulated from political pressure but equipped with a broader set of tools, would target inflation without relying exclusively on interest rates. That might include selective price controls, targeted taxation or transitional measures which recognise that a short period of mild inflation can sometimes be preferable to deep economic scarring.

The OBR would widen its mandate from fiscal orthodoxy to national sustainability in a richer sense: not only debt, but resilience. If a policy threatens the future of the NHS or transport system or energy security, it would be obliged to raise concern just as firmly as it does about debt projections.

Finally, an independent Office of Regulation would prevent regulatory capture and ensure that essential industries: energy, water, media, transport, are run for public benefit rather than shareholder extraction.

Why this matters now

Large transformation projects: repairing public services, decarbonising energy and housing, renewing infrastructure - are often good for the country but not instantly good for the Treasury’s short-term balance sheet. Under today’s wiring, those projects are choked before they start. Rewiring creates the institutional conditions for national renewal to be politically and economically possible.

The UK does not lack ingenuity, public demand or economic potential. What it lacks is a state architecture that allows good ideas to come to life. Britain is not doomed to decline; it is simply organised for decline. Change the wiring, and progress can resume.

This article is adapted from an original piece by Mark E. Thomas (November 2020). If you’re interested in reading the original piece you can find it here: https://99-percent.org/re-wiring-for-progress/.

For more analysis of the UK’s economic and democratic challenges—and to join a movement working peacefully to end mass impoverishment - sign up with the 99% Organisation.